F-stop F-stop For Mac

The Lens’ Aperture/f-stop is a diaphragm The aperture is a mechanical diaphragm inside the lens that opens and closes to create a larger or smaller hole; it’s an iris. The scene that you’re photographing (light) passes through this hole before it hits the sensor. You can set the aperture wide open to form a large hole, closed down to form a small hole, or anywhere in between. You’ll learn why you’d change the size of this hole in just a shake.

Remove the lens from your camera and look through the bottom end of it-you’ll see the aperture, which appears as a diaphragm formed by overlapping blades that expand and contract. The photo below is very important to understand.

The aperture opens and closes not smoothly, but in very specific increments. These specific increments are the true definition of the term “f-stop”. Lenses typically have 7 f-stops. Each f-stop has an alphanumeric name.

The naming system is backwards; Large f-stops are named with small numbers, and small f-stops with large numbers! A large aperture was needed to blur the background and separate the Dragonfly from blades of grass Have you ever seen a shot of an Elk in a forest, where its head was sharply focused, but the trees were fuzzy and “blurred-out”?

That effect was achieved by controlling the Depth of Field with the f-stop. Depth of Field refers to how much of the photo is sharp on either side of the actual plane that you’ve focused on. (Depth of Field is also greatly affected by lens focal length and distance, but that’s a separate blog). If a large aperture is used (when the “hole” is wide open), less of the photo will be in focus. In a portrait where the face is in sharp focus, but the background is smooth and blurred out, a large aperture can achieve that.

Remember, a large aperture has a small number. If a small aperture is used, more of the photo is in focus. In a photo of a wildflower where the flower is in sharp focus, and the distant mountains are also still mostly in focus, a small aperture was used. A small aperture has a large number. Furthermore, a medium aperture can be used in situations discussed below. To straightforwardly explain what the f-stop does without a bunch of distracting exceptions, this info works. However, it’s not quite this simple.

As I elaborate on later, shooting very close limits Depth of Field, where even a small aperture yields a blurry background, and shooting far away gives great Depth of Field, where much is in focus even with a large aperture. The f-stop also Controls the amount of light that hits the sensor As a side effect of opening and closing, a large aperture allows more light to hit the sensor to expose the picture, and a small aperture lets in less light. Consequently, this is a problem that needs to be compensated for.

If you let in less light with a small aperture, your photo will be too dark unless you add light somewhere else (and vice versa). So where do you add or subtract light? If you close or open the aperture, you have to lengthen or shorten the Shutter Speed Your first option to add or subtract light is to adjust the, making it faster or slower. Where the f-stop/aperture controls how much light hits the sensor, Shutter Speed controls how long light hits the sensor. Shutter Speed is the length of time that the shutter that hides the sensor stays open to expose the sensor to light when you take the picture.

A faster Shutter Speed means less light, and a slower Shutter Speed means more light. So if you make the aperture smaller to gain more depth-of-field, you’ve just subtracted needed light from exposing the picture. Now you have to lengthen the Shutter Speed to allow more light to hit the sensor.

Conversely, if you open the aperture wider to give a blurred background, you’ve added too much light. Now you must shorten the shutter speed to prevent that extra light from hitting the sensor. Luckily the camera can do this for you in various auto modes, but I recommend regularly shooting in Aperture Priority Mode. Or you can increase or decrease Your second option to add or subtract light is to adjust the ISO.

ISO refers to how sensitive the sensor becomes to light. It’s how readily or not the sensor “absorbs” light, so to speak. A high ISO is more sensitive to light, thus needs less light to properly expose the photo. A high ISO lets you use a smaller aperture or faster shutter speed to expose the photo. A low ISO is less sensitive to light and requires a larger aperture, or longer shutter speed to properly expose the photo. Adjusting either Shutter Speed or ISO both exert an array of effects on the photo which I’ll discussed in separate blog entries.

The shutter speed in particular has virtually infinite permutations to choose from that can have a profound effect on both the motion and sharpness of a photo. To get the foreground flowers and mountain both in sharp focus I used a small aperture of f/16. The Aperture, and ISO collectively expose the sensor to light. The amount of light they let in must add up to exactly 100% of the light needed to properly expose the photo. If you subtract light via one setting, you must add it back with one or both of the other settings, otherwise the picture will be underexposed.

Because there are many possible adjustments of each of the 3 settings, the combinations are practically limitless. Each combination makes the photo look different, which explains why you must master the technical side of photography to harness the creative side. Understanding “Exposure Value/Stop” You now know that a bigger f-stop lets in more light than the next smallest f-stop, but how much light??

A particular f-stop lets in exactly twice as much light as the next smallest f-stop, or one “Exposure Value” more light. For example, “f/2.8” lets in one Exposure Value more than “f/4”. Exposure Value is simply 1 unit of light, regardless which camera setting we’re discussing. A shutter speed of “1/125th second” lets in 1 Exposure Value more than “1/250th second” because it’s twice as long. ISO 100 is only half as sensitive to light as ISO 200, therefore it’s 1 Exposure Value less. To simplify, you can also just call an Exposure Value a “Stop”.

You do need to master Shutter Speed and ISO, but First concentrate on how the f-stop affects your pictures and let your camera take control of setting Shutter speed by shooting on “Aperture Priority”. After you’re comfortable with Aperture, move on to. Adjust the f-stop (Do this! ) If you don’t already know how to set your camera’s shooting MODES and manually adjust the f/stop, bust out your manual and figure that out now (it should only take a moment). Set your camera’s MODE to “Aperture Priority”. Now start adjusting your f-stop up and down. Look at the f-stops in the picture below and notice how they match the f-stops being displayed on your camera’s LCD as you adjust them.

You’re making the aperture inside the lens open and close. You will see unrecognized numbers that don’t match the sequence below as you cycle between f-stops. These are “1/3” stops, which you can ignore for now, and truthfully serve little purpose in landscape photography. Also, the f-stops on your particular lens might not go as large and small as those listed here.

Side-by-side comparison of Depth of Field created by each f-stop. This macro lens has a very small minimum aperture of f/32 Should I choose a Large, Small, or Medium Aperture? You now know that shooting with large aperture can blur the parts of the photo that have not been focused on, and a small aperture makes more of the photo in focus. Your aperture choice, therefore is largely creative preference. Sometimes you get little choice over the aperture because low light forces you to use a large aperture, for example. To instinctively choose which apertures work best for different subjects, you just have to experiment with every f-stop, and then compare the results.

Here are some basic guidelines for choosing your aperture. They are not rules!. In a landscape shot with close foreground elements, and distant objects like mountains, you’d want great depth of field: use a small aperture like f/16. In a shot of an animal in a forest surrounded by distracting leaves and branches that you want to blur out: use a large aperture like f/5.6 or less. In a “flat” landscape shot where most objects are the same distance away: use a medium aperture like f/8. In very close macro shots with lots of depth: use a small aperture like f/22.

Generally try to use a medium aperture whenever Depth of Field doesn’t matter because lens image quality is best at medium apertures!.At small apertures like f/16 and f/22 beware of diffraction, explained below Using the largest or smallest f-stops produces visual problems The largest apertures (f/5.6 and bigger) suffer from two problems on most lenses. One is light fall-off, which shows itself as vignetting; darkened corners of the photo. Vignetting isn’t such a big deal and you can fix it easily in post-processing.

Large apertures, particularly on zooms, can also cause the image to be soft in the center instead of razor-sharp. That means that no matter how precisely you focus, your subject will look slightly out of focus. The small Apertures (f/16, f/22 and higher) suffer from diffraction, which decreases resolution across the frame. It means your photos won’t be quite as sharp. Depending on the lens and size of your sensor, diffraction may not be very noticeable, and the increased depth of field from using a small aperture may justify a small amount of diffraction. Diffraction becomes worse with smaller sensors.

On micro 4/3 cameras for example, diffraction usually becomes very noticeable at f/11 and above. Shooting Close/Far Changes Depth of Field and Changes the Rules. At very close focus distance the Depth of Field is extremely narrow.

Here, even at the small aperture of f/22, the background is still blurred and only a 3mm slice is in focus. The closer your lens is to the subject, the less depth of field there is. That means that the closer you get to the subject, the plane that remains in focus will become thinner so there will be a blurred background even with small apertures. How does this affect which f-stop you choose? Let’s say you’re shooting a macro (extreme close-up shot) of a flower with the lens only 8″ away. You would need to use the smallest aperture just to get most of the flower in focus, and even then the background will still be out of focus. If you photographed the same flower at 8″ at the LARGEST aperture, only a scant slice would be in focus.

That’s not a bad thing if that’s the look you’re going for. The closer your subject, the shallower the Depth of Field. You might be inclined to use a large aperture to blur the background, but when shooting close, you need a small aperture just to get the subject itself in focus. The reverse is also true; the further your lens to the subject, the greater the Depth of Field. Say you’re hiding 200 ft. Away shooting Yeti with a telephoto lens with the Himalayas in the background.

Even with a large aperture of 2.8, the mountains are still going to be mostly in focus, even though using this aperture would blur the background at closer distances. Now if you moved to within 10 ft. Of Yeti and focused on him, the depth of field decreases dramatically and the Himalayas will be largely out of focus-even using a small aperture. Fast Lenses A fast lens means that it has a big maximum aperture. For example, a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 or f/2.8 would be considered fast (or f/4 on a super telephoto). A lens with a maximum aperture with f/5.6 or less is considered slow. Fast lenses are bigger and more expensive than slow lenses.

For example, the huge telephoto lenses on football sidelines aren’t that big because they’re as powerful as they look, they’re bigger because they have a fast maximum aperture to let in more light. They also cost $10,000! For a fraction of that cost, you can get an equally powerful zoom lens, but it will have a slow maximum aperture, and be smaller in overall size. I’ve read every word, what do I do now?

Put your camera in “Aperture Priority” mode and start shooting things at every aperture. Then compare the images to see how the different f-stops make each photo look different.

You’ll get some blurry images until you learn Shutter Speed and ISO, but we didn’t land the first man on Mars without a few tries did we? After you’ve learned Aperture, move on to.

F-stop F-stop For Macro

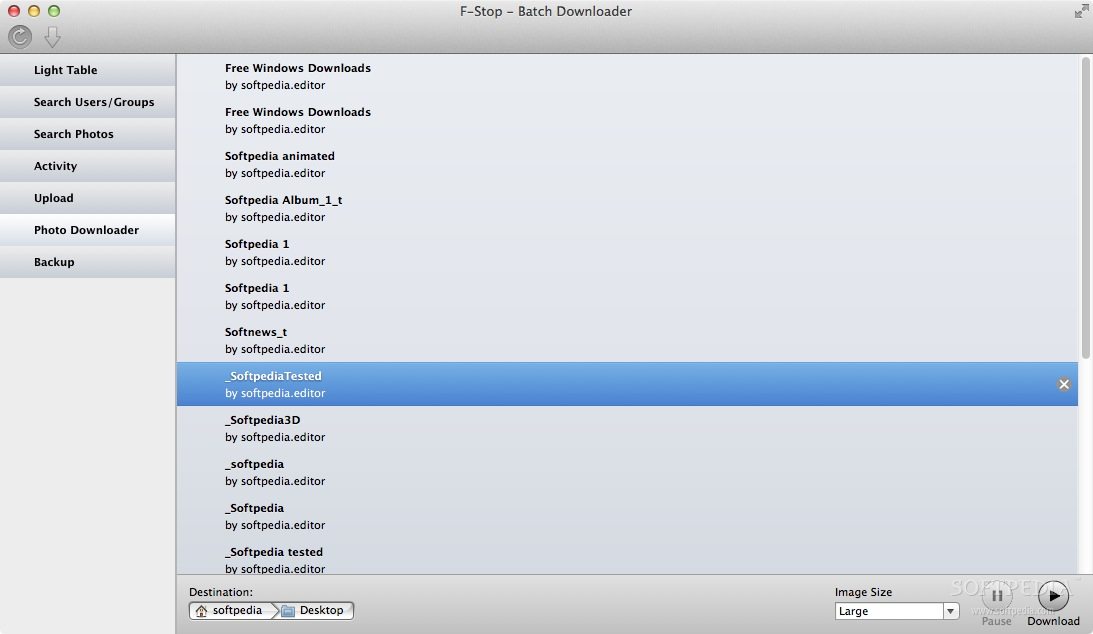

F-Stop (was Flicker1) is a Flickr client that allows users to browse Flickr in a simple, clean and intuitive way. Features. Browse all your stuff. View photo details. Monitor your Flickr activity.

Upload your photos. Make and save your own searches. Display account statistics. Add notes to photos. See geotag information over maps.

Reorder images inside your sets. Update photo metatags. Add remove/comments. Share your beloved photos on Twitter Note: A Flickr account (normal or pro) is What's New in F-Stop. F-Stop (was Flicker1) is a Flickr client that allows users to browse Flickr in a simple, clean and intuitive way.

Features. Browse all your stuff. View photo details. Monitor your Flickr activity. Upload your photos. Make and save your own searches. Display account statistics.

F Stop Formula

Add notes to photos. See geotag information over maps. Reorder images inside your sets. Update photo metatags. Add remove/comments. Share your beloved photos on Twitter Note: A Flickr account (normal or pro) is required.